Simón Díaz playing the Venezuelan cuatro, image courtesy of La Verdad

By Gustavo Nucette Fabelo

Of all of the public figures to emerge from Venezuela in the last century, none can claim to be as singularly influential, renowned and universally loved as Simón Díaz (1928-2014). With a career spanning several decades and a multitude of creative avenues, the prolific folk singer came to be synonymous with his nation’s culture. And yet for someone of his stature, his beginnings were remarkably humble, being born in the rural town of Barbacoas in the llanos, or plains, of the country, to a relatively poor family. This setting would form an integral part of his career, even long after he left it. The first of 8 children, at the age of 12 upon his father’s death he became the main provider for his family, setting each of his siblings up on their way he was finally able to pursue his own career in the entertainment industry of the capital, Caracas. Over the next few years his fame would steadily grow in film, television and music, but it was not until well into his career that his defining moments would come.

Díaz’s musical prowess was hardly accidental. From his humble rural beginnings, he had a deep appreciation for music and composing, crediting his mother with the opening line of the iconic Tonada De Luna Llena. Finally, in 1949 as a youth in Caracas he began studying at the Escuela Superior de Música de Caracas under the tutelage of Vicente Emilio Sojo, a renowned composer. It was here that the young Díaz consolidated his technical knowledge, laying the foundations for the meticulousness that would come to define his work.

Simón Díaz, image courtesy of simondiaz.com

Although by 1974 the public was well acquainted with Díaz, perhaps the seminal moment in his artistic trajectory came with the release of his album Tonadas, a collection of songs rooted in the Venezuelan folk style of the same name. The tonada is a type of folk song intrinsically linked to the llanos from which Díaz himself hailed, typically accompanying the daily work of farming. The folk music of Venezuela is also highly representative of its ethnically diverse population and various cultural influences. As such it is a genre firmly rooted in the history of the country and its people, the significance of which was not lost on the composer.

Whilst Díaz had recorded many albums of Venezuelan popular music using traditional instruments such as the four-stringed cuatro, Tonadas was decidedly different. It was the first album that brought his lyrical creativity and poetic fervour to the fore. Being the first album made up entirely of his own compositions and assuming a sombre, poetic tone, the record weaves his skilful cuatro playing with wistful remembrances of the idyllic countryside and the fading way of life it was home to. In particular songs such as Tonada Del Cabestrero, Tonada De Luna Llena and Mi Querencia invoke a strangely haunting beauty.

This air of gravitas firmly distances Tonadas from the playful zest of previous albums and was instrumental in elevating a disappearing oral folk tradition into eloquent, sophisticated artistry. Everything from the painted album artwork to the assertive, single word title indicates this shift. Moreover, the originality of the composition injected fresh life into the genre, asserting it as a living tradition rather than just a thing of the past.

Part of the understated significance of Simón Díaz is the extent to which he was able to capture tradition, culture and landscape into a powerful national iconography. Uniquely Venezuelan imagery permeated his music and even his very appearance. He was famously rarely seen without his liqui liqui, the traditional formal outfit of the country worn by men. On a more profound level his lyricism, with its constant reference to the rich natural beauty of his home and the stories of the ordinary people who inhabited it, is what carried the most importance in his music. National symbols such as the turpial bird, the araguaney flower and countless others litter his music, powerfully evoking a deeper sense of connection to the land. This pairing of emotional depth, shared tradition and being anchored to the environment is what made and continues to make Díaz’s best work so captivating. As one interviewer put it, he effectively transformed his native landscape from being simply a place on the map into a veritable spiritual experience and a source of immense pride.

Simón Díaz performing in his liqui liqui, image courtesy of The Times

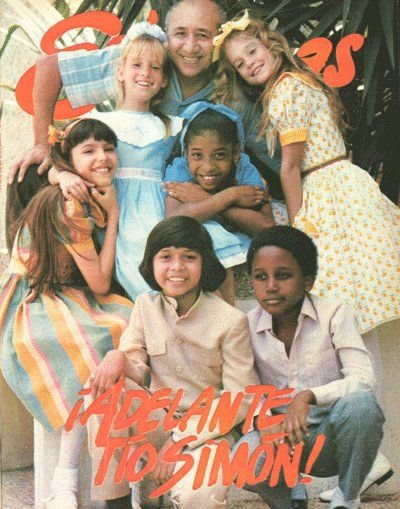

Equally instrumental in establishing Díaz’s position as the embodiment of Venezuelan culture and artistic respectability was his nature as an affectionate figure far removed from the divisive world of politics. Throughout his career Díaz remained true to his affable and wise llanero image, which served as a cornerstone of his initial success in entertainment. More importantly, in the 80s with the advent of his Contesta Por Tío Simón television program, he became a definitive fatherly figure for the nation. Running for over a decade, the kids’ show earned him the affectionate moniker of Tío Simón, meaning Uncle Simón. Contesta Por Tío Simón was centred around songs and educational content, all involving a group of 4-6 children affectionately known as his nephews. If Díaz was already emblematic for his illustrious musical career, then this show cemented his fame as a national icon among the widest possible audience. As a program with a target audience of children and families, it defined his image as a universally loved figure for contemporary and subsequent generations.

The cast of Contest Por Tío Simón posing for a magazine, image courtesy of Estampas

Contesta Por Tío Simón, image courtesy of El Nacional

He persistently eschewed political categorisation, with his image instead radiating authenticity, affection and love for his country and its people. His love for his country was expressed not in a nationalist or political sense, but rather in the way he exuded genuine appreciation for its natural beauty, culture and art. Part of the reason he is remembered so fondly is for his genial, affectionate manner and his elegant simplicity. An oft-quoted moment is his television appearance during the polarising 2002 national strike, in which he sang a song urging both President Chavez and the opposition to listen to each other, perfectly encapsulating his image.

The prestige Simón Díaz enjoyed during his lifetime is a testament to the influence he had on the national consciousness, but also the extent to which he was able to carry this far beyond the borders of his country. His work has enjoyed the coverage of some of the most renowned artists in Latin America and beyond, such as Mercedes Sosa, Julio Iglesias, Caetano Veloso, Marco Antonio Muñiz and many others. In 2008 he was awarded a Latin Grammy Lifetime Achievement award for his work, while at home he was the recipient of countless other awards throughout his life. He performed in some of the most prestigious venues worldwide such as Carnegie Hall and the Barbican Centre and continues to be recognised as a national treasure by Venezuela’s most prominent cultural figures. The reverence he enjoys speaks to the indelible mark he left.

Gustavo is a third-year History BA student at King’s College whose interests lie in political culture in Germany’s Weimar Republic, identity formation and diasporas