By Antonio Pinto

I first encountered Matías Piñeiro when he moderated a Q&A with Hong Sang-soo during his retrospective at Film at Lincoln Center. Piñeiro ditched the conventional Q&A format and instead encouraged Hong to play games of association. This resulted in a conversation that touched on Hong’s films in oblique yet revealing ways. Piñeiro’s playfulness evidenced a conscious effort to break away the rigidity that can develop in a conversation of this sort and opened up new avenues for approaching Hong’s work.

When I finally started watching Piñeiro’s films recently, I realized that the same unpretentious, almost mischievous approach he’d taken with Hong is employed in them. Piñeiro’s films are approximations to Shakespeare and his plays in a determinedly unacademic way, characterized by association rather than reproduction or explanation. They generally depict a group of women who are engaged in the Bard’s work (mainly through performance but also translation), and whose lives mirror in allusive ways the plays and characters they work with. The least vague way to put it is that they're adaptations of an incredibly loose sort. The traces Shakespeare’s plays leave on the films are in the cadence of the voices, a sense of dramatic irony and thematic concerns such as time and identity. The interplay between Shakespeare’s plays and actors in the modern world allows Piñeiro to craft films that are daringly inventive, resulting in freewheeling cinematic experiences.

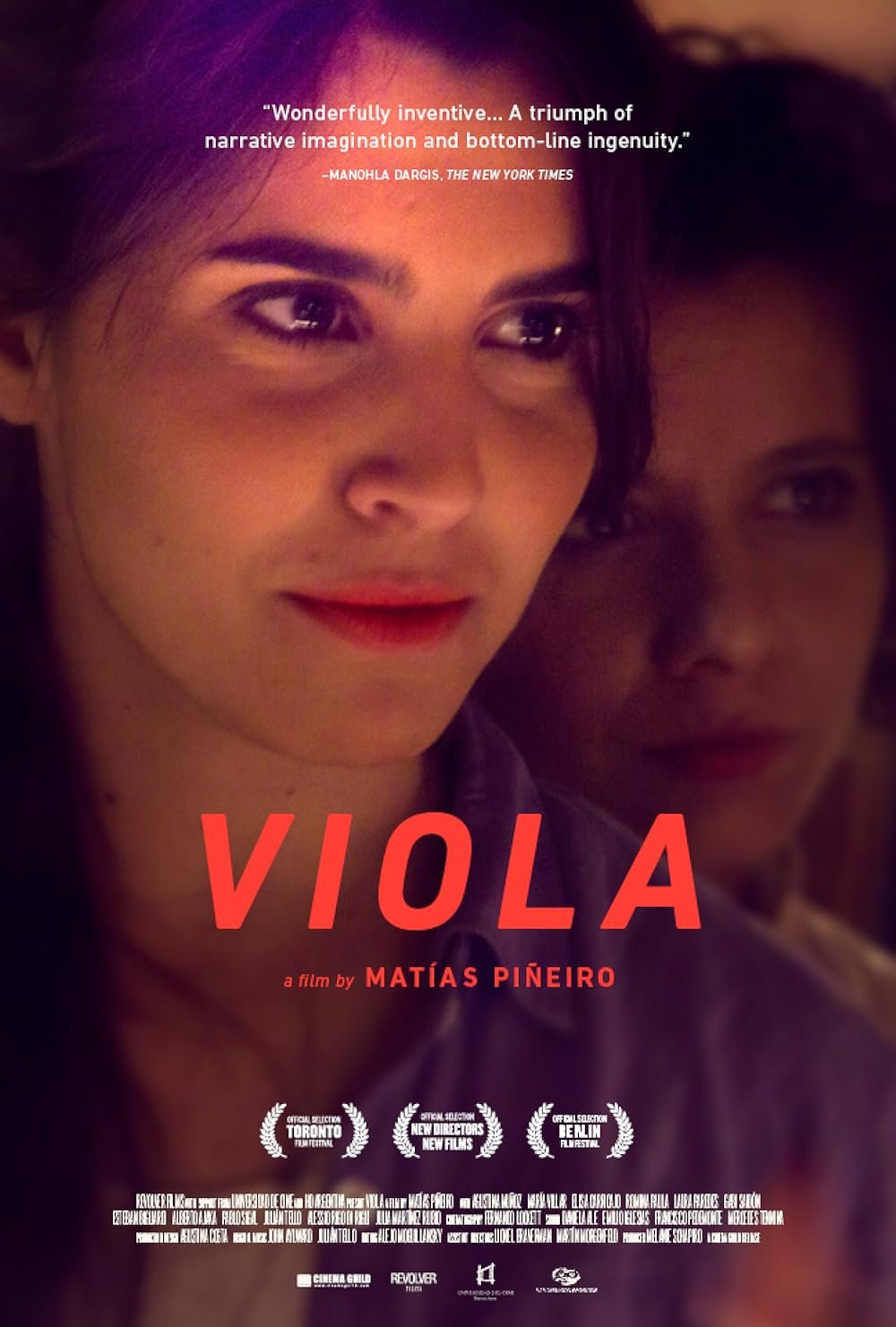

Viola (2012)

In Viola (2012), a young woman delivers pirated DVDs to clients in Buenos Aires. One of her clients tells her an anecdote of the romance between two actresses performing an adaptation of Shakespeare together. At the end of the day, she stumbles upon this very theater group and is offered a role in their play. When she heads back home, she has developed an acute awareness of performance and uses it in relating to her boyfriend. Seemingly simple, the film however relays the story of the two actresses' romance in a long introductory sequence and is structured around strange, almost magical coincidences. The displacement of what seemed the main character for another suggests a hidden logic at work in the film – a logic that is simultaneously veiled and engaged throughout the film.

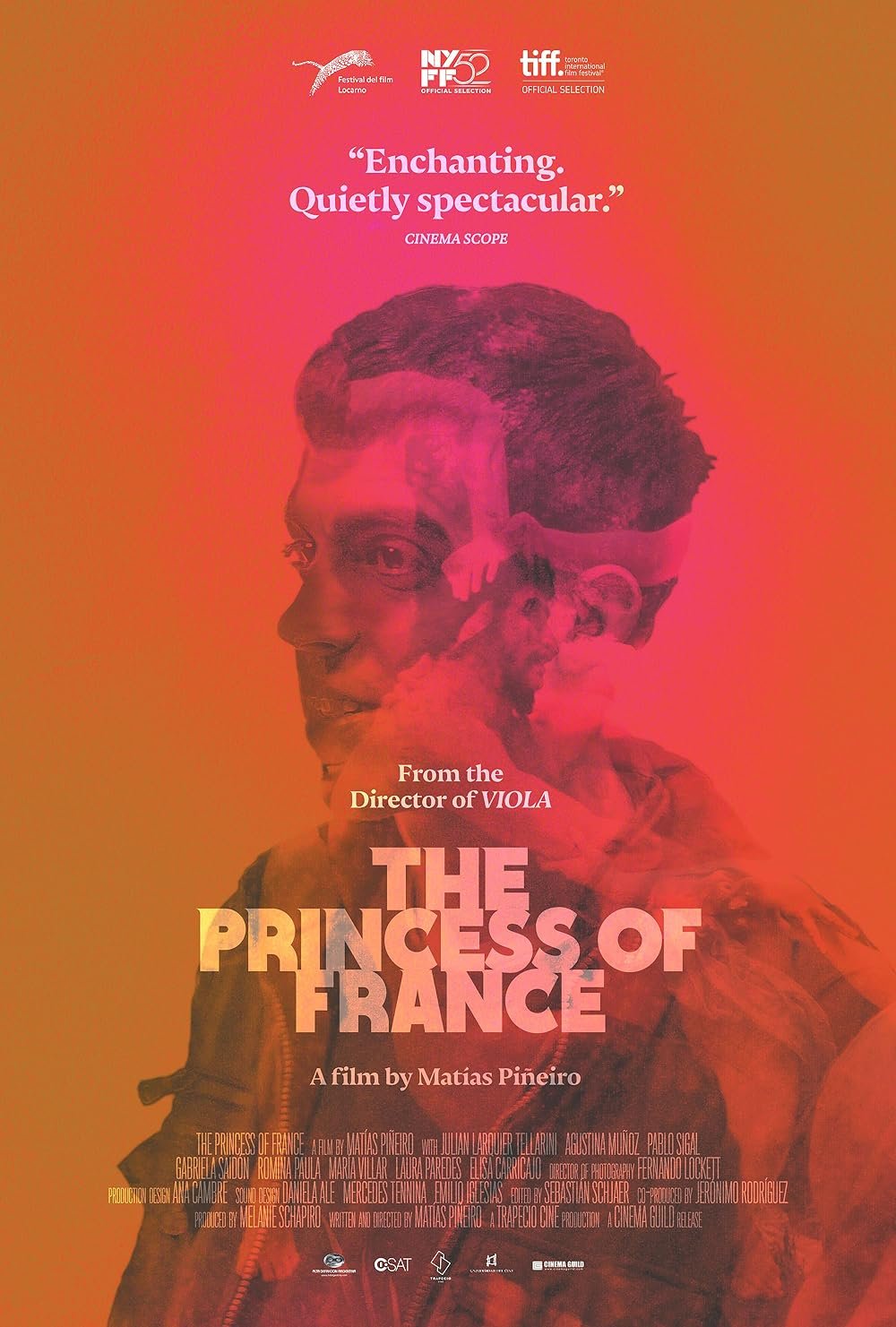

La princesa de Francia (2014)

In La princesa de Francia (2014), a young actor returns to Buenos Aires in order to put on a radio adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Love’s Labour’s Lost.” Upon arriving, he is entangled in the romantic dynamics he had left behind when he departed. He has varying degrees of relationship with almost the entire group of actresses he works with and the film seems to purposely confuse the identity of his lovers. Some sequences are repetitive like dreams and one romantic moment is explicitly wishful thinking. Unconcerned with closure or fixed identities, the film instead explores the space between reality and fantasy that Shakespeare’s comedies open up.

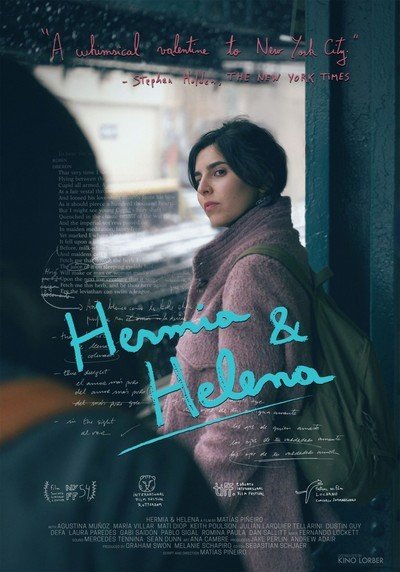

Hermia & Helena (2016)

Like Viola, Hermia & Helena (2016) begins with one character in order to migrate to another. In this case, they are both Argentine thespians in a fellowship at an art’s institute in New York. When Carmen’s time at the institute is over, she is replaced by her long-time friend Camila. They coincide briefly in Buenos Aires in what becomes a long day of preparation for Camila’s departure. Carmen explains the ins and outs of the institute to her friend, and in the ensuing months the parallels and departures between the two friends’ experiences generate a playful game of identification. This process also relates to Camila’s task as a translator and interpreter. She has to translate her life in Buenos Aires to New York – and in New York, Carmen’s experience is a sort of original text which she has to translate for herself. Told in three cycles, each exploring a different facet of Camila’s life, the structure of the film feels like an exercise in interpretation as well, in which each reading (or cycle) reveals the different plots in her life.

In constructing these films, Piñeiro deliberately avoids the strictures of conventional narrative or realism. Instead, taking after Shakespeare, the films use language, choreography and props to create polyphonic, labyrinthine games. The long, panning shots, the superimposition of texts and images, and the inclusion of paintings in these films demonstrate that filmmaking has a much wider breadth of resources at its disposal than what is normally in use.

Still from La princesa de Francia

Antonio Pinto (Lima, 1995) studied Hispanic Literature and Linguistics in the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Since 2021 he has been living in Brooklyn, NY, where he writes and makes films. He posts regularly about film on his newsletter Eddie Cusik. Currently, he is developing his first feature film.