By Darla Timewell

The 13th of March, Cinema Mentiré (https://www.instagram.com/cinema.mentire/) and the ICA organised the London premiere of The Human Surge 3, directed by Eduardo “Teddy” Williams, who stayed for an insightful Q&A after the film. The screening of a non-commercially driven Argentinian film like this on the big screen is highly significant, considering the restrictions on the film industry that the current far-right Argentinian government imposes, severely cutting funding for public sectors such as the arts. Darla, film student who was present at the premiere, presents her thoughts on the film.

The Human Surge 3 will be showing at the ICA from the 5th of April (https://www.ica.art/films/the-human-surge-3).

Argentinian director Eduardo Williams returns with his latest feature, The Human Surge 3 (2023).To preface this review, I will admit that I have not seen the previous instalment, The Human Surge (2016). But I don’t think that matters too much, considering the fragmented and disjointed nature of the film. Fragmentation, disjointedness but also continuity and cyclicality are the structuring devices of this film. The film expresses this dynamic through both form and content, through the glitchy distortions of characters’ faces, which seem to break up yet also blend into their surroundings; through the 360 degree camera, which is similarly distorting, whilst moulding and melting the edges of the very world around it as it moves; through the unstructured narrative which seems to hop from country to country, yet transport each of its characters with it; or through the seamless communication between characters, who talk in Spanish, Tamil, and Mandarin, though all seem to understand each other.

Williams creates a highly surreal vision of the world and human interaction, yet the bizarre logic of the film is normal and naturalised within its diegesis. I think what is interesting about the world of The Human Surge 3 is that it is as if the visual quirks and immateriality of the internet became material. The possibilities that the internet presents us with, the global connectivity and communication that transcends national and physical boundaries, becomes realised within its frames. In one sequence we see certain characters wander around Sri Lanka, and in the next they are at a train station in Taiwan, seemingly as confused as us. By the end of the film, many of the characters from each of the locations are united on top of a mountain, where, as if it were normal, some people are flying —which reminded me of playing multiplayer Minecraft in creative mode. At one point, the group of friends begin to exclaim that a girl’s face has squares all over it, and, indeed, we watch her pixelate. These are occurrences that seem totally nonsensical in the context of a mountain hike with physical bodies, but would make complete sense if you were playing a video game over a video chat with friends. The national boundaries and language barriers of the material world are things that digital culture allows us to transcend, and something that The Human Surge 3 transcends via its digitally informed post-cinematic aesthetics.

Despite the science-fiction-like logic of the film, the narrative is surprisingly relatable and grounded in everyday experiences. The characters hang out and complain about their jobs. They engage in youth culture and talk about their lives. They wander the malleable landscape, which is manipulated by the effect of the 360 degree camera. As Williams explained in the Q&A after the film, during production, the cinematographer wore a backpack which held the camera, which allowed them to move around the space more freely and with greater mobility, with no need to direct the lens. This means that what was recorded during production was a sort of Google Maps-esque panorama of the entire space. Recording this way allows Williams to capture people more organically situated within their environments, with less intrusion of the logistics of framing and organisation of space that a more conventional film set demands. As a result, the interactions between the people that populate the frames feel naturalistic and quotidian. And the quotidian is really the beauty of this film. At the Q&A, an audience member commented that we live in a culture where voyeurism of the wealthy elite dominates media production. The director responded that he isn’t interested in that, but rather in making films about what most people in the world look like and do with their time. So, we are presented with an eclectic mix of cultures and people, but linked by their particular socioeconomic position. “Shame is to be a multimillionaire,” a phrase repeated by many different characters throughout the film, becomes emblematic of a vision for a world in which the lives of the global elite are decentred in favour of a working class majority. Digital culture holds the potential to erase these hierarchies of visibility.

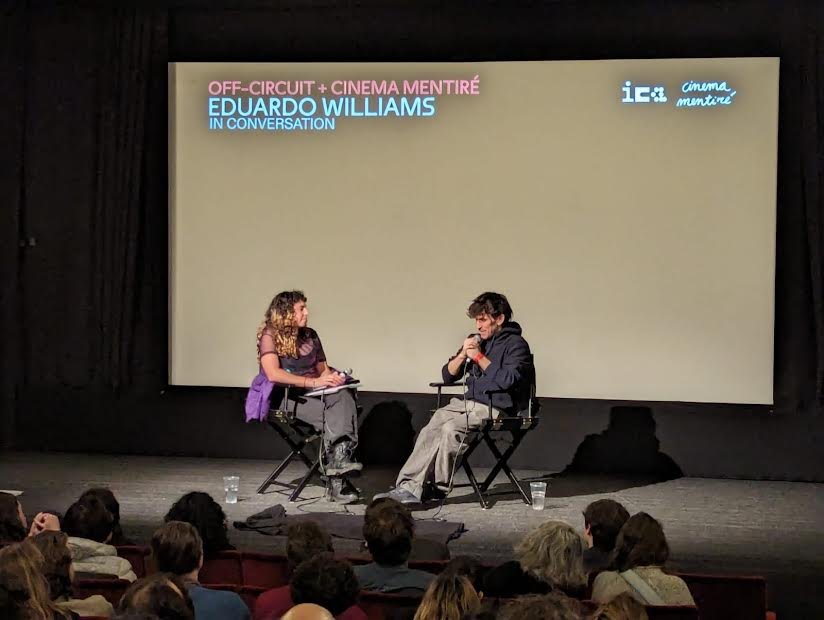

Q&A with Teddy Williams at the ICA premiere. Photo provided by Cinema Mentiré

Sound is also a crucial element of the film. Williams explained that in most films the ambient sound is lowered in favour of human voices, but the director likes to reverse this process. The result is that the hierarchy of animal, nature, and human sounds is flattened, and the characters become even further situated in their environments. Not only are class hierarchies erased, but also the hierarchies between the human and the non-human.

In terms of editing, the 360 degree panorama footage was later explored by Williams in post-production using a VR headset, with which he looked around the recorded space, choosing what fragments of it would appear on screen by directing his look. A kind of retroactive direction of the frames after the fact, influenced by sensory reaction and instinct. So, in a way, Williams becomes director and spectator simultaneously. Choosing where to look and what to see articulates our experience of contemporary visual culture, as spectators are no longer limited to the singular perspectives of the traditional cinematic experience. This device, which also encourages the spectator to allow their gaze to wander the screen, reflects how moving image culture now also comprises interactive video games and social media platforms which one can exercise a certain amount of agency over. The Human Surge 3 understands that the contemporary spectator is a digital flaneur.

The film is undeniably post-cinematic in its aesthetic as it complicates and distorts linear perspective. The narrative could be described as a network narrative, in its linkage of disparate people and locations. The characters wander through a perpetually overcast world —the lens of the camera almost always dotted with specks of rain that melt objects together. The achievement of The Human Surge 3 is that it explores and articulates the experience of living in a material world mediated by a digital perspective. An experience of fragmented subjectivities, yet also previously unimagined connectivity. Paradoxically, the film shows, it is fragmentation itself which gives rise to a new experience of connectivity.

Halfway through the film an earthquake ripples through Peru, Sri Lanka, and Taiwan —an instance of a material experience that connects every character. Isn’t it crazy to think that a single vibration of the earth can be felt by so many people at once? The shock of the earthquake instigates a serene moment in the film, where the camera gazes up at the sky and trees in the Amazon rainforest in Peru. The light peaks through the tree leaves, and the camera begins to swirl, slowly at first, then faster and faster. The circular movement of the camera distorts the light and leaves, which blur together into a pixelated fractal-like image. It's kaleidoscopic. You can’t tell where objects begin and end. A beautiful, intense image, suggestive of all the elements in the world melting, dissolving, breaking up, to become one. The boundaries between beings erased. Everything as one single wave and rhythm. All breathing, together at once. A human surge?

My understanding of The Human Surge 3 is one that is informed by the positive aspects of digital culture —in the film, I see a hopeful vision of the world, as the internet connects the global working class, and enables us to articulate and participate in a radical vision of community. The internet certainly has its pitfalls, and the 360 degree cinematography could, on the flipside, be read as emblematic of societies of control and surveillance. As much as the internet connects, it also alienates. However, I think what Williams expresses so beautifully is the idea that the technology we use does not have to be used for monetary gain. In a time of technological anxiety, arising from the rapid transformation of technology which impacts our day to day lives, Williams reminds us that it's not the technology itself which determines our social conditions, but the ways we use them, and the ways in which our societies are structured. There are alternative ways in which society can be organised, and different ways that power can be distributed. Ultimately, The Human Surge 3 articulates a vision for a mode of existence and experience which resists the demands of capitalist ideology, where people are free to wander wherever they wish, and direct their look at their will.

Darla Timewell is an undergraduate Film Studies student at King’s College London. She has worked as an assistant programmer for BIFA qualifying short film festival EFN, and hosted KCL Radio podcast Deep Fried FM. She is currently writing her dissertation on caves in cinema, and wishes she could crawl into a cave forever.